Chess, these days, has become quite mechanical. If you want to work on an opening, switch on Komodo 9 or Houdini 4 and start preparing with a 3200 rated assistant. If you have played a tournament game and want to analyze your mistakes, the same silicon monster will come to your assistance. Though extremely useful and almost indispensable, it was this very engine that had started to give me a nauseatic feeling whenever I sat down to work on chess. The computers gave me the correct answers all the time, but they made me lazy and the solutions were often just too difficult for my mind to assimilate and master. Even the books that I would try to pick up to read had variations checked through a computer. Perfection was what all the authors were aiming for, but this very search for flawlessness had made the game of chess quite boring, dull and drab for me. So in June 2015, when Quality Chess published the English version of Tigran Petrosian's best games with annotations by the ninth World Champion himself (atleast half of the games) I immediately realised that this could well be the panacea that I was looking for.

Python Strategy is the republication of the Russian book "Strategy of Soundness" written more than thirty years ago. Petrosian couldn't finish the book due to his ill health but he had already annotated a significant amount of games which form the basis of this book. A few other games have been annotated by top grandmasters and close friends like Isaak Boleslavsky, Igor Zaitsev and others.

The ninth World Champion, Tigran Vartanovich Petrosian, was one of the greatest positional players ever to have played the game of chess. (Picture source)

What is it about the book that I loved so much? The annotations by Petrosian were usually done immediately after his game had ended for magazines or newspapers. This meant that his annotations were mainly word based with the inclusion of deep variations only when required. Such kind of annotations may not be perfect (like computer analysis) but they teach you a lot about the game. It's like getting to peek into the mind of a great player. Let me illustrate this with the first encounter in the book, a game that was played in 1945 when Petrosian was just 16 years old.

Tigran Petrosian vs Nikolay Sorokin

White to move. What would you play?

Let's see what Petrosian has to say about this position. More than the move it's his comments that made a deep impression.

Petrosian's explanation: "Now the plan of b2-b4 and Na4 is not all that dangerous to Black, since his own knight will land on c4. Nonetheless Black's scheme has a major defect: he has "shelved" the task of developing his kingside pieces and castling. At that time I had already mastered one of the important laws of chess strategy: if one side has fallen behind in development the game must be opened up to punish the offender."

With this insightful explanation Petrosian played 12.e4! intending to meet 12...Qxb2 with 13.Bd2 with dangerous threats. In this book, Karsten Mueller has presented the last chapter which consists of around 10 pages and entitled "Under the Microscope of the Computer." He analyzes a few of the games from the book using the engine and showing where Petrosian missed some of the moves like in the position above after 12.e4! Qxb2, a strong move would be 13.Nxd5! exd5 14.exd5 when the black king is stuck in the center and the queen is not to safe on b2. While this analysis showing the truth is important, I think it's Petrosian's comments which are more important to be assimilated. Take for example one more position from the next year-1946.

Vladimir Dunaev-Tigran Petrosian

It's Black to play here. What would you play -12...Rc8 or Rb8 ?

In the game Petrosian played 12..Rc8 but he condemned the move with the following words.

Petrosian's explanation: "If Black had foreseen the following events, he woud have played 12...Rb8! White cannot do without advancing his g-pawn (g2-g4), and in consequence Black will have to play ...Nc5, freeing d7 for the other knight. To meet the attack on the e4-pawn, and with the assurance that d6-d5 will not be playable, it is highly likely that White will exchange on c5, leading to the closure of c-file. This analysis would have prompted Black to ensure that his rook was "in the right place" (Rb8), not formally but in substance."

What a joy it would be to see the greatest attacker Mikhail Tal (left) and the greatest positional player Tigran Petrosian (right) analyzing the same position (picture source)

I could go on and on about the beautiful explanations that Petrosian has given in this book but then the review becomes too long and no one buys the book!

One thing that made me relate to Petrosian quite instantly was that the fact that he developed his game through hardwork. In the introduction Nikolay Tarasov wrote, "It is said that the genius Capablanca learnt to play chess by watching others play. Petrosian was not able to do this. He looked at the chessboard for hours, but the laws of this game remained incomprehensible to him."

Being a person who learnt the rules of castling and en passant after many days of playing, this felt good to read!

Another story which really touched me was the follwing, "Tomorrow, for the last time, they (Tigran and his brother Amayak) are going to get up at four in the morning, shivering from the cold; they are going to open the door cautiously and then run to the grocery store on the corner. There will be plenty of people there already. But the boys have no need to be first. Everyone huddling in the street at this early hour, in front of the closed doors of the shop, thinks that this is a queue for meat. But for Tigran and Amayak it is a queue for.... a chess set! At seven in the morning they will sell their "turn" in the queue to grown-up stange women for two roubles, and in their secret chidren's money-box the necessary sum will finaly come together to realize their long standing dream of taking taking the 31 roubles to the sports shop and buy a chess set - a large genuine set with wooden board and heavy lathe-turned pieces."

What passion for the game!

It was exactly this passion that led Petrosian to study his first chess book - Nimzowitsch's Chess Praxis again and again for three to four times, get back to the chess board within a few days of his father's death, practice chess for hours in spite of the work and responsibility on his shoulders since the age of fifteen and it was exactly this passion that made him a World Champion in 1963 which he retained for six years!

The 1963 match between Petrosian (left) and Botvinnik (right) ended in a win for the former with a score of 12.5-9.5. You can find 27 seconds of video footage of the 1963 match on Youtube.

Contribution to Opening theory

It was said that Petrosian fed his family because of the King's Indian Defence! Not because he was a big expert in it from the black side but because he almost always crushed it with the white pieces. One of his favourite systems has his name engraved on it in opening books.

The usual way in the Classical Variation of the King's Indian is to 7.0-0 but Petrosian would almost always push his pawn 7.d4-d5 and later follow up with Bg5! These games in the King's Indian show you how good his positional understanding was. This variation came to be known as the Petrosian system.

This little rook pawn move is something that Petrosian liked against the Queen's Indian and was later on used extensively by Garry Kasparov. Nowadays we call it the Petrosian-Kasparov system

There are many more opening systems that have developed thanks to the efforts of Petrosian but I would like to draw your attention to how this book can help you to build your understanding in the first phase of the game.

The Torre Attack which is played with 1.d4 2.Nf3 and 3.Bg5 was one of the favourite systems of Petrosian with white. Here is one position that was reached out of that opening.

Tigran Petrosian vs Victor Liublinsky

What would you play as White?

Petrosian's explanation: "An exchange of bishops would be wholly senseless. The pawn on e5 is cramping Black's position - and any exchange, reducing the quantity of pieces on the board, would alleviate his lot. After all, the fewer pieces there are, the less space is needed for manoeuvring. Apart from that, after 10.Bxe7 Qxe7 11.f4 or 11.Nf3, Black could start an immediate attack against White's pawn wedge with 11...f6. Hence White must play 10.Bf4!

Now if 10 .. .f6, the reply 11.Qh5 is most unpleasant for Black. It forces 11...f5, as 11...g6 would be met by the obvious sacrifice 12.Bxg6 hxg6 13.Qxg6+ Kh8 14.h4. White's threats are then scarcely to be fended off- for instance, 14...fxe5 15.Qh5+ Kg8 16.Bh6 Rf6 17.Rh3!"

After this paragraph we understand how important it is to conserve the bishop on f4. Look at the balance of words + variations in the annotations.

After seeing the above example, let us fast forward a few years to 1966 when Petrosian is defending his title against Boris Spassky.

Petrosian and Spassky played two matches against each other in 1966 and 1969. In 1966 Petrosian was successful in defending his title with a score of 12.5-11.5 and in 1969 Spassky won with 12.5-10.5. (picture from www.worldchesshof.com)

In the seventh game surprisingly Spassky employed the Torre Attack with the white pieces. After 11 moves we reach the following position:

Boris Spassky vs Tigran Petrosian

Black to play

Petrosian's explanation: "White is following a familiar path. The pawn is transferred to e5, and the dark-squared bishop is retained for the coming fight. But there is one very big "but". Black has not yet castled, and this, at bottom, denies White any prospects for using his e5-pawn as an active instrument. On the contrary, White's advanced post becomes an object of attack. However much the commentators might have raged afterwards, it would have been more sensible to steer the game into a placid channel by exchanging bishops on e7, following with f2-f4, and renouncing ambitious plans."

Petrosian played 11...Qc7 and later 0-0-0.

Where on earth would you get such pearls of wisdom?

Petrosian was quite well known for his positional exchange sacrifice. These examples are pretty well known and I would direct you to the beautifully written book called

Learn from Legends by Mihail Marin also from Quality Chess. There is an entire chapter on Petrosian's exchange sacrifices with in-depth analysis. Of course, these games do exist in this book also but I very much liked some of the more subtle positional decisions made by Petrosian. For example his game against Anatoly Bannik from 1958.

Tigran Petrosian- Anatoly Bannik

How should White increase his advantage?

White is clearly better here thanks to the passive bishop on e7 which is inhibited by its own pawns on e5, f6 and g5. A very natural continuation is 1.Bxb6 axb6 2.g4. This would secure the knight on e4 and would give White a small edge. But Petrosian goes for 1.Bc5!!

Petrosian's Explanation: "In deciding on this move, it was imperative to weigh all the "pros" and "cons" thoroughly. The move looks illogical as White is voluntarily exchangin his "good" bishop for his opponent's "bad" one, instead of swapping bishop for knight (18.Bxb6+) and securing his preponderance. However, if you probe into the position a little more deeper, it becomes obvious that after a possibe exchange of rooks on the d-file and the transfer of king to e6, Black would cover his vulnerable points and create an impregnable formation. The role played in this by the "bad" bishop would be of no small importance."

After 1.Bc5!! Rxd1 2.Rxd1 Bxc5 3.Nxc5 White was threatening infiltration on e6 and after 3...Re8 4.Ne4 Re6 5.g4! He was clearly better as the f6 pawn is very weak.

There are such positional themes littered all over the book. An alert and discerning eye will quickly learn from them and add it to his positional arsenal.

Apart from this there are also a few interviews of Petrosian which have been compiled. The clarity of his answers makes it a very enjoyable read. An interviewer asked Petrosian "Who was your teacher?"

Petrosian replied, "My teacher number one was life itself. Teacher number two was the now deceased master Archil Ebralidze , who taught chess in the Tbilisi Pioneer's Palace. Then came Capablanca, Nimzowitsch.... and after that it was a case of 'caling at all stations,' as they say; I learnt from everyone I happened to encounter at the chessboard and I did a lot of reading."

The Candidates final between Petrosian and Fischer in 1971 was won by the American by a margin of 6.5-2.5. While this might seem a huge margin, the match was very interesting with some closely fought games.

A year before their Candidates match Fischer and Petrosian played each other in the Match of the Century in Belgrade. Petrosian lost the match 3:1. A wonderful gesture by Petrosian was annotating game two of the match in great detail. It is rare to see a lost game being added to one's collection of games.

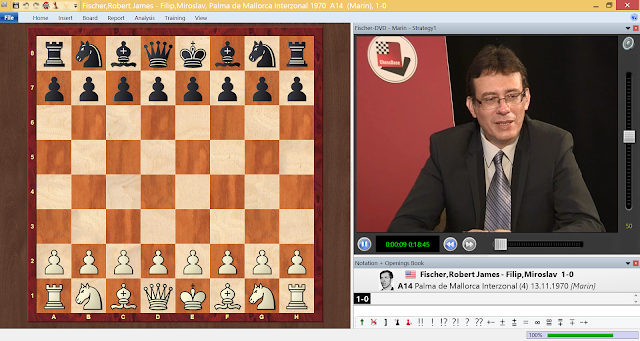

What is the best way to study this book? Of course you can open the book and start reading and playing over the analysis. But for maximum benefit I suggest the following approach:

1. Open the game in the book that you want to study and check the names of the players.

2. Search the game in Mega Database and open the game in training mode in ChessBase.

3. Set up a chess board, take the side of Tigran Petrosian, and guess his every move. In this way you are in the shoes of the champion. If your decision is different from Petrosian's try to understand the reason for it. It could be possible that you came up with a better solution.

4. After you have seen through the entire game check the analysis from the book. It might be possible that some of your doubts are cleared. If they are not then discuss with your friends or coach and finally if there is no one, switch on your 3200 Elo assistant!

The above way of working with the book will take quite some time for studying each and every game but at the end you will not easily forget the games and ideas that you have learnt for many many years.

Conclusion: Tigran Vartanovich Petrosian used to hardly lose his games. Thanks to his sense of danger and prophylactic play he could avert the problems much before they would arise. It was for this reason that people started calling him the "Iron Tigran." Lev Polugaevsky famousy quoted, "In those years, it was easier to win the Soviet Championship than a game against 'Iron Tigran'."

This book helps you to not only know about one of the greatest legends of the game but in doing so you will unknowing experience a sudden rise in your positional understanding. Don't ask me how it happened! Those are just Petrosian's blessings for studying his games carefully!

I heartily recommend it.